Special Issue on Immigration

Short Story

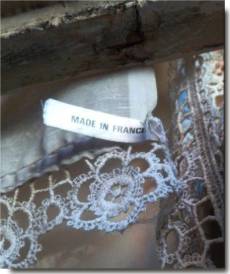

Made in France Clermont-Ferrand, France © 2010 Christine Spadaccini |

Fundraising Drive: Dear readers, it's that time of year again. We need to raise $2,500 in the next three months. Without this amount (in addition to what we have already received), we won't be able to maintain Swans with the quality and dependability you have grown used to over the years. Ask yourselves the value of our work, and whether you can find a better edited, more trenchant, and thoughtful Web publication that keeps creativity, sanity, and sound thoughts as first priorities. Please help us. Donate now!

(Swans - October 4, 2010)

This is the end of a beautiful party. Summer.

See all the confetti scattered everywhere on the ground?

Dead leaves.

This is the end of my painful panting. Last hour.

See the lone "Spaghetti" battered on his bed, heaven-bound?

Dad leaves.

Son, I've asked you to push the head of my bed under the window so I can feel the hand of autumn on my sore face one more time, feel its fingers of wind breathing through my deflated hide and help me lift it, maybe. But I'm too tired already to even pop my head up and look outside. All I can see lying here, out of breath, soaked with perspiration, urine and fading hopes, is a little ray of morning sun ricocheting on the sill and drawing a faint pastel rainbow on the cornered horizon of old wood, pale plaster and flowered lace that is to be my last. Since you dragged me here, I've been wondering what's written on the drape's tag that is gently floating above me, my eyes won't tell me no more...

I came to France at the end of the year 1957, long before you were born, son, with just one suitcase of twined cardboard under my arm: inside were my Sunday suit neatly folded, a white starched shirt, a black tie, and a pair of leather shoes. Those were for special circumstances, dancing, and funerals. The rest of my clothes, I was carrying on me, under a heavy coat of coarse wool. It was late autumn, the train was cutting through a grim, already frozen landscape, and all along this forlorn journey I found solace in eating the goodies zia Giulia, my nice little aunt, had packed for me, her sweet way to say good-bye, food she thought I was unlikely to find up here, in distant foreign France, and would dearly miss: dried sausages of donkey meat, a big chunk of parmigiano cheese, and a bag of twelve persimmons. The fruits were very ripe. I was to eat them quickly. It took me a long time, a full day almost, to reach my destination, at the speed of half a persimmon an hour, memories of home and my leaving it forever linked to the fruit's flavor, both so delicate and pungent. And through it all, the trip, the munching, my life, I kept on thinking about the story Giulia loved to tell us kids over and over, of Geppe the shoemaker and the orchard of persimmon trees.

A long time ago, in our mountain, lived a shoemaker. He was a very gifted craftsman. But also the poorest man of the village. Anyone coming over to his little shop and showing a desperate need for a repair or a pair of new shoes was sure to get it at the prize of a few judiciously shed tears and, as you can imagine, a-plenty they came, sobbing and begging. Because the shoemaker's heart was so tender and kind and the ground so harsh and cold in our place he had made it his life's mission that no one around him go barefoot or suffering from bad shoes. But for his job he barely ever got paid: most people around were really poor, it's true. But, believe me, they were meaner than poor! When they saw that Geppe, the shoemaker, was such a good soul, they just took on the habit of making fool of him and had him work for naught. He was living with his old mother in a shack at the end of the dirt road. Not many travelers ever came through our village, so remote it was, up in the valley, except for gypsy caravans, from time to time. But the "Zingari" were not welcomed: people in the village said they were only coming to rob chicken and children and seduce wives away with the melancholy of their music. So they chased them ruthlessly. Once, a gypsy family came knocking on Geppe's door, trying to escape the rain of stones that was the way the villagers used to greet them with. He let them in, offered shelter and spent the night making shoes for the kids. The father had warned him that he could not pay. Geppe had smiled. He knew! But how on earth could he let these kids walk around in the cold barefoot?! Before the family left early the next morning, the father thanked Geppe and said: for your kindness, please, take these, they're special. He put a handful of what looked like seeds in the shoemaker's hand and was gone. Geppe went back inside and was greeted by his mother's sneer. And what did you get for your job this time? Show me! A handful of dry beans! You, dweeb! She took the seeds from the shoemaker's hand and before he knew she had thrown them furiously through the window. The following day Geppe and his mother woke up to a strange new landscape: where, hours before, in the front of their house, were just barren soil and desolation, an entire forest had spawned! In the course of a single night a magnificent orchard of trees covered with strange orange-colored fruits had grown from the handful of gypsy seeds...

Believe it or not, son, but I barely had time to get out of the train that work began. As soon as my feet touched the French ground, they gave me a pick, a shovel, and I started to dig and dig and dig. One hole. Big hole. Then more holes, big, big holes. One after another. Graves. All the first morning I dug, all the first day I dug, and all mornings and all days that followed up, on and on and down and down, I dug... I have dug graves all my life, you know. Even my own, it's ready, you'll just have to drag me up there and write my name and dates on it...

But let's get back to that first morning... At noon, after the digging, we went to the restaurant.

The boss introduced me to the waiter.

- Salut, l'nouveau! What's your name?

- Paolo Spadoni.

- Shit, Roger, you've brought one of these "Macaroni" again!

Back then, "Macaroni" was the generic name for Italian workers in France, men from the land of pasta and pizza, cheap, hard-working, disposable, and laughable labor.

- So what do you want, mister "Spaghetti"?

- My name is Spadoni, mister.

- Spadoni or spaghetti, same thing!

- Are you really sure you want to try spadoni? I'm about to serve you some. "Al dente," if you see what I mean...

- Oh, okay, okay, take it easy, Spa-DO-NI. Was just kidding. No offense. Better get used to it, though...

He sure was right.

Geppe went out to the miracle orchard, creeping cautiously along, unsure his eyes were telling him the truth. But, no doubt, the trees there were real ones. He reached out for a fruit, pulled it, felt it, smelled it, pressed on its skin. He was bringing it to his mouth when he realized the whole hungry village was watching him. He waved at them. Come, help yourself! His words were like a long awaited signal. People and animals rushed under the trees and started to gorge on the sunny persimmons. Soon the feeding frenzy ended as there was not a single fruit left on the trees! About as quickly some began to complain: my lips, they feel strange, they burn. Me too, my mouth tingles. I'm not feeling right. A kid started to cry, more stomachs to gurgle and hurt, a donkey lied down, a woman threw up. Poison! Someone yelled. Geppe and the Zingari, they have poisoned us! Geppe knew this was not the time for discussion but for running.

I settled in France. There were more pasta names, more Paolo Spaghetti, Mister Panzani, Signore Macaroni, Monsieur Bolognese, and more and more digging. I thought of my village in Italy often, I missed the strange sweetness of persimmons. They did not grow here, it was too cold during winter. I knew I would go back one day but not the same poor man I was when I left. I wanted to show them I had made it big, that I had become someone. Some kind of enriched macaroni made in France...

So the poor shoemaker had no other choice but run for his life and after the Zingari, hoping they would give him the persimmons' antidote which he thought was the only way to be allowed to return among his people. He followed them down the Peninsula on a trail of poisonous orchards and delusions, stopping only to mend shoes when he needed money. Months and years went by. The Zingari were nowhere to be found. He got weary of his wanderings, thought he could settle in one of the pleasant cities he kept crossing on this way and establish a little shoe repair shop, find a girl, live his life, finally. But in each place he tried to make his dream come true, people wouldn't let him: they were suspicious and jealous, he was a stranger, both feared and mocked, one of the "Polentone," "eater of polenta" as they contemptuously called those hailing from northern Italy. Life became such a heavy burden that one day he attempted to get rid of it. He had come across one of these gypsy orchards again: beautiful trees all spruced up, like for Christmas, with the bright orange little spheres dangling from the branches. He sat under one and sadly began to eat a fruit... 'til Death do us "tart," he thought, as an acid taste began to pervade his mouth. The first persimmon was not ripe enough, the reason of Geppe's distaste. But the next one was a pure marvel and the following felt even better... What a tasty way of dying, he thought. And he fell asleep. He woke up to note that paradise looked every bit the same as the persimmon orchard he had just left. He was just feeling a little queasy from too much eating. Well, right, Geppe had not died and the persimmons had never killed anybody. It was time for him to go back home...

First thing when I finally made it back, years later, I ran to my mother's bar and almost yelled my order at her, so excited and happy I was to whirl the old words out of my mouth again and listen to their familiar melody in the air:

- Campari con bianco. Uno per due e presto!

- Hey, who do you think you are? Our people first! Then you, il francese!

When Geppe arrived, he found his mother busy picking up fruits in the persimmon orchard in front of their old house. He was worried she would not recognize him. So many years had passed since he had fled the village. The answer came, blunt, a blow:

- Always hiding when there's work to be done, you lazy moron! Hurry up here, Zingaro, and give me a hand!

See, son, in France I was never French. My macaronic talk always gave me away. And in Italy I was Italian no more. I had given away the magic orchard of childhood and family bounds. At least, in Death, I will be dead! Sounds like I've finally found the place where I belong! Along with all the "Macaroni" callers, all the Zingari, all the workers from all over the world, all the bosses, all the racists, all the gravediggers, all the saints, all the lucky, all the unlucky, all of you, just everyone...

- Papy...

- What?

- Why did you leave Italy back then?

- No jobs. Not enough to eat. Misery.

- And why did you stay here, after?

- My children were born French.

- I've been called pasta names too, you know, Papy...

- I bet.

- Your family in Italy really had an orchard of persimmon trees?

- Si.

- What do they taste like, the persimmons?

- Well... Sweet but not so much, very unlike what you can expect, it's strange. Don't know how to say it really... By the way, can you tell me what's written on the curtain's tagup here?

- Made in France.

- Made in France, that's what you said?!

- Yes... why?

- Well... Sort of funny to think of me ending with this tag "made in France" pinned above my foreign body...

- Papy, you're not...

- I am, son, and I am going to tell you what persimmons taste like now.

- Like what?

- Irony, son, "mac-irony"!

Jump to the next short story by Fabio De Propris.

If you find Christine Spadaccini's work valuable, please consider helping us

Legalese

Feel free to insert a link to this work on your Web site or to disseminate its URL on your favorite lists, quoting the first paragraph or providing a summary. However, DO NOT steal, scavenge, or repost this work on the Web or any electronic media. Inlining, mirroring, and framing are expressly prohibited. Pulp re-publishing is welcome -- please contact the publisher. This material is copyrighted, © Christine Spadaccini 2010. All rights reserved.

Have your say

Do you wish to share your opinion? We invite your comments. E-mail the Editor. Please include your full name, address and phone number (the city, state/country where you reside is paramount information). When/if we publish your opinion we will only include your name, city, state, and country.

About the Author

Christine Spadaccini on Swans -- with bio. (back)