Book Review

|

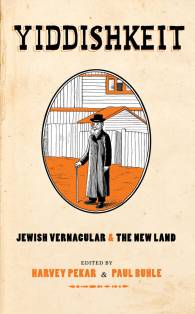

Yiddishkeit: Jewish Vernacular & the New Land, edited by Harvey Pekar and Paul Buhle, with an introduction by Neal Gabler, Abrams ComicArts, New York, September 2011, ISBN 978-0-8109-9749-3, 240 pages, $29.95 (hard cover).

(Swans - August 29, 2011) The French are very defensive of their language. The government runs a General Commission for Terminology whose mission is to frenchize, or gallicize, foreign words and expressions. For instance, words like e-mail, computer, or software are not considered kosher. Instead, French, and Quebecers too, advocate the use of respectively courriel, ordinateur, or logiciel. In contrast, English is a much more flexible and hybrid language that has always welcomed and incorporated foreign words (including, ironically, thousands of French ones). As Ralph Waldo Emerson once put it: "The English language is the sea which receives tributes from every region under heaven." Not long ago, I saw my status of a mentsh, whose opinion was "immensely valued," relegated to that of a shmendrik, or worse, a schmuck. It felt like being hit by a 90 mph curveball. It hurt. I didn't respond in kind, thinking, oy vey, but this maven, this yiddisher kop is mishpocheh -- he is family. Nu? This little anecdotal glitch (or the usual shund one gets over and over undeservedly) serves the purpose of highlighting words (1) that should be familiar to anyone who lives or has lived in places with large Jewish communities, like New York City -- Yiddish words and expressions that have entered the popular culture. Franz Kafka is reported to have said after watching a Yiddish play: "I will tell you, ladies and gentlemen, how much better you understand Yiddish than you imagine." But how did these words -- and there are many more -- get sprinkled into American English?

The answer can be found in the immaculately printed and superbly illustrated comics art anthology, Yiddishkeit: Jewish Vernacular & the New Land edited by Harvey Pekar and Paul Buhle. Both authors are uniquely qualified to lead the readers through a fascinating story. Harvey Pekar, who passed away in July 2010 and is famous for his American Splendor series of autobiographical comic books, grew up in a Yiddish-speaking family and spoke the language in his youth. Paul Buhle, who has written, edited, and coauthored over 40 books, learned to read Yiddish three decades ago as he was researching the history of the radical left, which led to his creation of the Oral History of the American Left project at New York University and his 1987 Marxism in the United States, based to some degree on Yiddish sources. He conducted multiple interviews with aged leftists, many of them Yiddishists, and was able to listen to their answers in the language. He has written or edited numerous books on Jewish culture and politics (2) and collaborated with Harvey Pekar on at least six projects. (3)

In a brief introduction, author and film critic Neal Gabler explains that Yiddishkeit is much more than just a culture, a feeling, a sensibility, or a language. It is a way of life, a Jewish way of life, "an essential part of both the Jewish and the human experience." Allen Lewis Rickman relates "an old Israeli joke" that encapsulates the deepness of the notion:

On a bus in Tel Aviv a mother's talking to her kid in Yiddish, and the kid keeps answering in Hebrew. The mother keeps trying to get the kid to answer in Yiddish, and finally an Israeli sitting next to them says, "Why don't you just let the kid speak Hebrew?" She says, "Because I don't want him to forget he's a Jew." (p. 128)

This is Yiddishkeit!

In this short 240-page book, Buhle and Pekar, with the collaboration of writers and artists such as Barry Deutsch, Spain Rodriguez, Peter Kuper, Sharon Rudahl, Dan Archer, Nick Thorkelson, Joel Schechter, Yelena Shmulenson-Rickman, et al., manage to offer an entertaining history of Yiddishland from its beginnings in medieval Europe to the Lower East Side in Manhattan, from its roots in the working-class, left-wing psyche to the fading of a language due to assimilation and multiple red scares, and to a recent revival thanks to the efforts of YIVO -- literally, the Yiddish Scientific Institute -- and others.

The book is organized in four chapters. The first one addresses the emergence of Yiddish culture and history along the Rhine in Germany and then Central Europe among Ashkenazi Jews. It explores Yiddish Classics, the Yiddish press, poets, novelists, singers, humorists, and the richness of its vast literature from the 1860s until World War II and 1948 when Stalin turned against the Jews and Israel was created and chose Hebrew as its official language. The scenes are at times tragic (poverty, pogroms), funny, nostalgic, and even romantic. The drawings are absolutely superb.

The second chapter focuses on Yiddish Theater and Film, first with a play written by Allen Lewis Rickman and illustrated by Gary Drum, "featuring the work of an awful lot of great Yiddish playwrights, lyricists, and composers," first performed in 2007: The Essence - A Yiddish Theatre Dim Sum. Suffice it to know that the play was designed to be "99 44/100% nostalgia-free" to understand that you are in for a real treat mixed with "irrelevant interludes" -- for instance, you'll learn that "Yiddish has literally hundreds of ways to say -- 'Imbecile'." Follows additional illustrated plays and comedies.

The last two chapters are shorter. Chapter 3 walks the reader around Yiddish & American Popular Culture before the assimilation of Jews into the American English language. It even has a guide to celebrities fluent in Yiddish (e.g., Molly Picon, Zero Mostel, James Cagney, Kirk Douglas, etc.) or performers who have used Yiddish (Mel Brooks, Groucho Marx, Paul Robeson, Woody Allen, etc.) -- but forget about Isaac Bashevis Singer: Pekar and Buhle do not hold him in much esteem. The final chapter examines the Yiddish fadeout in the second half of the 20th century and the recent revival through the work of various Yiddish institutes, the digitalization of thousands of books by the National Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts, and the indefatigable work of the Institute for Jewish Research (YIVO) in Manhattan.

The morning after I received an advance copy of Yiddishkeit I sat in my armchair, opened the book, and did not relinquish it -- except for calls of nature -- until I reached the last page, a 1976 portrait of Aunt Tania by Marvin Friedman. In less than a day I discovered a world unknown, yet fascinating. Neither pedagogic nor didactic, the scripts are superb, the drawings splendid, and as Paul Buhle wrote in his Editor's Note, "the culture of Yiddish is so inherently vernacular that comics art provides a perfect venue for an exploration of issues and personalities." A significant historical and cultural book not to be missed.

If you find Gilles d'Aymery's article and the work of the Swans collective

valuable, please consider helping us

Legalese

Feel free to insert a link to this work on your Web site or to disseminate its URL on your favorite lists, quoting the first paragraph or providing a summary. However, DO NOT steal, scavenge, or repost this work on the Web or any electronic media. Inlining, mirroring, and framing are expressly prohibited. Pulp re-publishing is welcome -- please contact the publisher. This material is copyrighted, © Gilles d'Aymery 2011. All rights reserved.

Have your say

Do you wish to share your opinion? We invite your comments. E-mail the Editor. Please include your full name, address and phone number (the city, state/country where you reside is paramount information). When/if we publish your opinion we will only include your name, city, state, and country.

About the Author

Gilles d'Aymery on Swans -- with bio. He is Swans' publisher and co-editor. (back)

Notes

1. Kosher = proper, legitimate (aside from the law of Jewish diet) -- mentsh = authentic, decent person -- shmendrik = fool -- schmuck = asshole -- oy vey = expressing shock and grief -- maven = expert -- yiddisher kop = intelligent Jewish person -- Nu? = Huh? -- glitch = problem -- shund = crap. (back)

2. For instance, Jews and American Popular Culture (3 volumes - 20 authors), Jews and American Comics, From the Lower East Side to Hollywood, as well as 5 books about the Hollywood Blacklistees (most of them Jewish), etc. (back)

3. They coauthored Students for a Democratic Society, The Beats, and Studs Terkel's Working, a Graphic Adaptation, and Pekar contributed stories for Wobblies! A Graphic history of the Industrial Workers of the World (reviewed on Swans), FDR and the New Deal, Jews and American Popular Culture, and finally Yiddishkeit, Pekar's "final sustained script-work." (back)