by Karen Moller

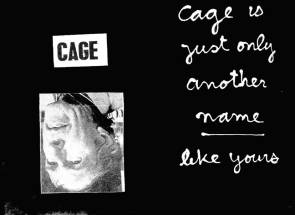

John Cage Painting by Ben Vautier © 1980 |

(Swans - June 20, 2011) A friend of mine mentioned John Cage to me in 1959 in San Francisco. She had wanted to study at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, but her parents had refused on the grounds that she would likely get into all sorts of trouble. "It was an unusual, experimental college full of extraordinary characters. People like John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg, William de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Robert Creeley were all there at the time," she said.

It was the first time I had heard of the people who would come to mean so much to me in the future. Later, when I heard Cage's minimalist music at a concert in Paris, I was totally captivated. I realized it was not only art that could revolutionize perception, but music as well. Cage's music, so close to purposeless play, had an absence of order, structure, and control that made me examine sounds in a new way.

In 1960, Jean Tinguely had an exhibition of his painting machines in Paris. I helped push his giant sculptures through the street to the gallery with many of my friends. Tinguely was a devotee of Cage and the idea of random art of pure chance. He believed that his painting machines created by pure chance because of the random nature of how and where the pen points or felt tips touched the paper. (The aim of creation by chance was to extinguish the artist's personality, his memory, his will, and even his desires.) The art his machines produced was totally uninteresting and in that sense the idea of chance creating art failed but the machines were remarkable. No doubt Tinguely came to the same conclusion, because the following year he dropped the idea and just created mobile sculptures.

In 1962, I met George Brecht, a highly talented artist with a work already in the Museum of Modern Art. He had been a student of Cage and was surprisingly articulate both about Cage and the Fluxus movement. According to him, the long-established art limitations were no longer useful and he believed like Cage that those boundaries needed widening. "Personally, I'm interested in using chance and humor to create a moment when the insignificant becomes other than insignificant." The more George talked, the more I had the vague impression he was thinking, well, not exactly backwards, but the opposite of positive. It felt like he was twisting my brain around and making me rethink everything that I had till then thought normal. His parting words were, "It is simply better to do less than more."

George was destined to be one of Fluxus most influential artists and my other friend, Robert Filliou, became, for me, the embodiment of the Fluxus spirit. But throughout those flourishing years of Fluxus, I never heard a better description of Fluxus than from my friend Emmett Williams, who was also a devotee of Cage. Here is a quote from his book, My Life in Flux -- and Vice Versa. The argument goes like this: John Cage was a student of Daisetsu T. Suzuki, the Japanese religious philosopher who helped to make the Western world aware of the nature and importance of Zen. In turn, many of the activists on the American Fluxus scene studied with Cage, who opened the Doors of Perception for some of them. Ergo: Fluxus has a direct connection with Zen. There is, of course, one important thing that the masters of Zen and the masters of Fluxus have in common: the extreme difficulty of explaining to the outside world exactly what it is they are masters of. Ultimately, there is only one way out of the Fluxus-Zen dilemma: the art of zenzen. "Zenzen allows you to have it both ways. It teaches us that Fluxus is totally involved with Zen, Fluxus is entirely involved with Zen, Fluxus is quite involved with Zen, Fluxus is completely involved with Zen, and, even more important, Fluxus is not at all involved with Zen."

Again I was struck by the contrariness of the explanation and the need to revise my thoughts. Statements like that were not unusual in those remarkable years of the sixties and as the years passed many of Cage's ideas were absorbed and found a more general acceptance among the public. In 1969, The 14 Hour Technicolour Dream, a pop-poetic event, was held in the Alexander Palace in London and twin stages were set up at the far ends of the hall where two separate groups played simultaneously. In the space between the two stages, at mid-points, was a rented fairground 30-foot helter-skelter slide that offered free rides to anyone with the courage to climb to the top. Under that shaky structure, in the central zone, the wholly random blend of the two opposing bands met and produced a throbbing and irregular heartbeat reminiscent of John Cage. As I stood listening, I remember thinking that he would have appreciated that weird, curious composition of accidental and totally arbitrary sounds created by pure chance.

Perhaps John Lennon's thought was similar when he stood in that central area with John Dunbar from the Indica Gallery. I saw him move back and then looking quite pensive he slowly moved forward. He stopped and put his hand up as if to say wait. "Did you hear that?" he asked. He turned and walked back through the audio fusion zone created by the sounds from the two bands from the opposite ends of the hall. He stood there for many minutes then nodded, and, perhaps in imitation of Hoppy's (John Hopkins, the great organizer behind the sixties events) much-used phrase, said, "Far fucking out."

And so it was.

If you find Karen Moller's work valuable, please consider helping us

Legalese

Feel free to insert a link to this work on your Web site or to disseminate its URL on your favorite lists, quoting the first paragraph or providing a summary. However, DO NOT steal, scavenge, or repost this work on the Web or any electronic media. Inlining, mirroring, and framing are expressly prohibited. Pulp re-publishing is welcome -- please contact the publisher. This material is copyrighted, © Karen Moller 2011. All rights reserved.

Have your say

Do you wish to share your opinion? We invite your comments. E-mail the Editor. Please include your full name, address and phone number (the city, state/country where you reside is paramount information). When/if we publish your opinion we will only include your name, city, state, and country.

About the Author

Karen Moller is the author of Technicolor Dreamin': The 1960's Rainbow and Beyond (Trafford Publishing, 2006, ISBN: 1-412-08018-5) and a fashion designer who lives half time in Paris, France, and the other half in Venice, Italy. (back)