math © 2014 Harvey E. Whitney, Jr. |

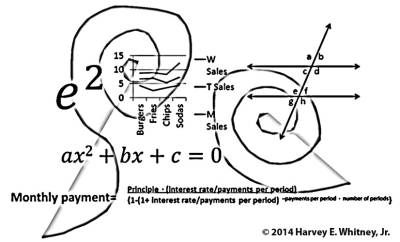

(Swans - March 24, 2014) As far back as classical civilizations, ethics has always been seen through the lenses of mathematics or the science of measurement. For example, the story goes that in the Egyptian afterlife, the soul or ka journeys to the underworld to eventually have his everlasting fate decided at the feet of Osiris. The heart of the individual is then weighed on a scale against the feather of virtue, the ma'at. Should the ma'at outweigh the heart of the dead, then the individual being judged will not go on to enjoy the fruits of eternal life but be damned: his heart snacked upon by Amemait, the crocodile-headed, hippopotamus-torsoed beast who anxiously awaits the results. Yet the point here is clear in terms of the relation of mathematics to ethics: the virtue of a person in the end can only be determined by measurement or calculation against a standard.

Other instances in intellectual and cultural history exhibit a close tie or metaphorical modeling of ethics to mathematics. Aristotle in his Nichomachean Ethics suggested that achieving good, the moral good, is to choose the mean, a sort of middle way between the vices of excess and deficiency. The term mean is a mathematical term that describes the average of numbers. In terms of the right course of action, the mean would constitute a sort of middle way between extremes or vices, such as desire and the refusal of desire when one is faced with the Oreo cheesecake that someone has brought to the faculty party. On the one hand, to inhale the entire cheesecake would be seen as a mark of gluttony and extreme selfishness in not being willing to share it with others at the party. On the other hand, to refuse the cheesecake would be seen by the giver of cheesecake as rude since she brought it for everyone's enjoyment, whether members of the party were on a diet or not. So the mean in this case would constitute taking a slice (or half a slice for the weight watchers) because the action would be a middle way: one avoids gluttony while also avoiding an unreasonable asceticism at a time when everyone is expected to indulge. What is perhaps problematic here is that we know that the mean refers to the average, although we know that with a set of numbers, the middle number is generally referred to as the median. Sometimes the mean and median are the same but that depends upon the distribution of numbers. We know that the mean of all of the whole numbers between 0 and 100 is 50 and the median is also 50. But the mean of 1, 3, and 7 is 3.667 and the median is 3.

In the early modern era, an era that saw the rise of science, there was an unyielding need to apply the study of numbers to all of life, and ethics was of no exception. Interestingly enough among the school of Continental Rationalists, Spinoza, who like Descartes, had a geometry fetish, wrote the Ethics, which is a series of geometrical-like proofs to demonstrate God's existence and the nature of reality and the (moral) good. Spinoza is well known for advocating pantheism in that work -- God is everywhere and everything, and the two primary attributes of God are extension and thought. This identification of God as everywhere and everything with the attributes of extension and thought puts to rest for Spinoza the mind/body problem that Descartes could not plausibly address (i.e., how does mind and matter interact) but also paves the way to a more just society. If God is everywhere and everything, then the result of that reasoning is the divine is in all of us: we are all equal in that respect, as well as all equal in being physical beings, extended through space, as well as being equal as thinking beings. A just society then recognizes each person's equality to the next person. Like in Aristotle's application of mathematical terms to ethics, Spinoza used a mathematical term/relation, "equal," as the basis of his moral theory. An action is just in recognizing one person's equality to you and vice versa; evil would constitute an abandonment of such recognition. Of course, we know that Spinoza, like so many other intellectuals of the early modern era, unfortunately did not think of women as equals. * But the geometrical proofs present in the Ethics and the equality of men all point to a moral system modeled upon mathematics.

Then there is the karmic principle, a facet of Buddhist thinking. The idea is that a good act toward another can only return goodness to you and likewise, a bad act can only return evil to you in kind: as if morality was some sort of circle of reciprocation. Of course this sort of thing doesn't quite square with the Western idea of good acts or acts intended to be good as paving the road to hell: a line to hell instead of a circle of reciprocity.

Of course these days, the measure of virtue seems to be a credit score: we've seemingly moved on from geometry and Newtonian mechanics in ethics to one in which virtue is to be measured by some sort of financial calculus that no one but bankers and financial industry analysts understand. Future employment, the ability to obtain a place to live, and the ability to obtain life insurance are increasingly tied to this financial hocus pocus that does not take into account sudden illness, an unexpected job loss, or macroeconomic factors in an economy that diminishes income, such as housing bubbles caused by banks trying to profit off of selling bad loans. It is this type of mathematics that we need to resist in determining a person's moral character, especially now since the economy is still trying to improve from the crash of 2007. Many people who have not found work, the long-term unemployed, have been refused work not only because they have been unemployed for a long time but because they have suffered financially due to being out of work. As a result, credit scores dip because there is no money to pay the bills. Many companies now, companies in which jobs are not tied to the handling of money, have been using credit reports to screen applicants. This needs to end for work that is not tied to the handling of money or finances. Additionally, studies have shown that there is no correlation between character and credit score.

Recently, Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts introduced legislation to stop this practice: a good move but I doubt that a Congress and president that provided bailouts to the financial industry in the Great Recession would actually get behind legislation that would help citizens reduce employment requirements that are tied to the very credit reporting industries that are propped up by the banking industry.

Just as the need to tie ethics to geometric, physics, and statistics have come and gone, we need to get beyond an ethics that measures moral character by credit score and the financial math that generates it. Those scores do not take into account individual circumstances that may be tied to forces beyond the individual's control.

* There is some debate over this as some scholars have claimed that in other writings, such as his Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, Spinoza thought women could be rulers and that he also thought that monarchial and aristocratic governments could be just: given certain safeguards. (back)

Please consider making a donation to Swans.

Legalese

Feel free to insert a link to this work on your Web site or to disseminate its URL on your favorite lists, quoting the first paragraph or providing a summary. However, DO NOT steal, scavenge, or repost this work on the Web or any electronic media. Inlining, mirroring, and framing are expressly prohibited. Pulp re-publishing is welcome -- please contact the publisher. This material is copyrighted, © Harvey E. Whitney, Jr. 2014. All rights reserved.

Have your say

Do you wish to share your opinion? We invite your comments. E-mail the Editor. Please include your full name, address and phone number (the city, state/country where you reside is paramount information). When/if we publish your opinion we will only include your name, city, state, and country.

About the Author

Harvey E. Whitney, Jr. is a doctoral candidate in history at Florida State University and teaches medieval and modern global history at Howard Community College in Maryland. To learn more, please visit his Web site at http://hewhitney.com/. (back)